From Crisis to Classroom: The Education Dilemma for Ukrainian Refugee Children in Poland

“We need policies that don’t just ask these children to adapt to Polish culture but also celebrate their home cultures. Maintaining their home languages while learning Polish is crucial for their success.”

Mandy Stewart, DSW, Professor of Literacy, Language, and Culture at Texas Woman’s University and Professor of Research at Uniwersytet Dolnośląski DSW

When war erupts, it doesn’t just disrupt governments and infrastructure—it upends lives, especially the lives of children. As Ukraine continues to endure the Russian invasion, its ripple effects have been felt across Europe, especially in neighboring Poland, which has become a temporary home for millions of displaced Ukrainian families.

For the Ukrainian children who have crossed the border, the trauma of war is compounded by the challenge of adapting to a new education system. While Poland’s schools are enforcing mandatory attendance for these refugee children, many hurdles lie ahead as both the students and the institutions adjust to the reality of integrating into the Polish education system.

Reports from UNICEF and UNHCR estimate that about 150,000 Ukrainian children residing in Poland have been unable to attend school in person, a significant concern given the nation’s policy of mandatory schooling. After years of remote learning and displacement, the transition from online learning to in-person education brings forward a new set of challenges for educators, policymakers, and students alike. These challenges raise a fundamental question: how can Poland ensure that these children not only integrate into its education system but thrive?

Meet the Expert: Mandy Stewart, DSW

Dr. Mandy Stewart is a professor of literacy, language, and culture at Texas Woman’s University and a professor of research at Uniwersytet Dolnośląski DSW.

She has authored and edited seven books on language and literacy. Among these are the practitioner-focused But Does This Work with English Learners? A Guide for ELA Teachers 6-12 and the critical research book Radicalizing Literacies and Languaging: A Framework toward Dismantling the Mono-mainstream Assumption. Additionally, she is co-editor of the English Journal with the National Council of Teachers of English.

Language Barriers and the Power of Biliteracy

One of the most immediate hurdles Ukrainian refugee children face is language. Many of these children are already multilingual, with proficiency in Ukrainian, Russian, and sometimes English. Yet, to succeed in the Polish school system, they need to acquire a new language—Polish—at a pace that allows them to keep up with academic expectations.

“There are highly trained, loving teachers in Poland who are capable of taking on this new challenge,” says Dr. Mandy Stewart, co-creator of Project Biliteracy. “But for these students to succeed, we must focus on affirming their home languages and cultures while helping them learn Polish.”

Language acquisition is not just a hurdle for the students but a challenge for the educational system itself. Poland’s education system is not designed to accommodate such a large influx of non-native speakers in such a short time. Before the war, Poland was a fairly homogenous society, with the school curriculum and teacher training primarily geared towards Polish-speaking students.

“Whereas countries like the U.S. have much experience in educating students new to the country, there was not as much of a need for this within the Polish educational system until more recently,” explains Dr. Stewart.

With the arrival of nearly a million Ukrainian refugees, including an estimated 800,000 children and youth, schools must now quickly adapt.

Project Biliteracy, a program designed to support refugee students while preserving their native languages, addresses this need directly. Rather than forcing students to abandon their mother tongues, Project Biliteracy emphasizes a holistic approach, integrating the students’ home languages into their learning process. This biliteracy model allows children to build upon their linguistic foundations, drawing from their lived experiences and gradually incorporating Polish into their education.

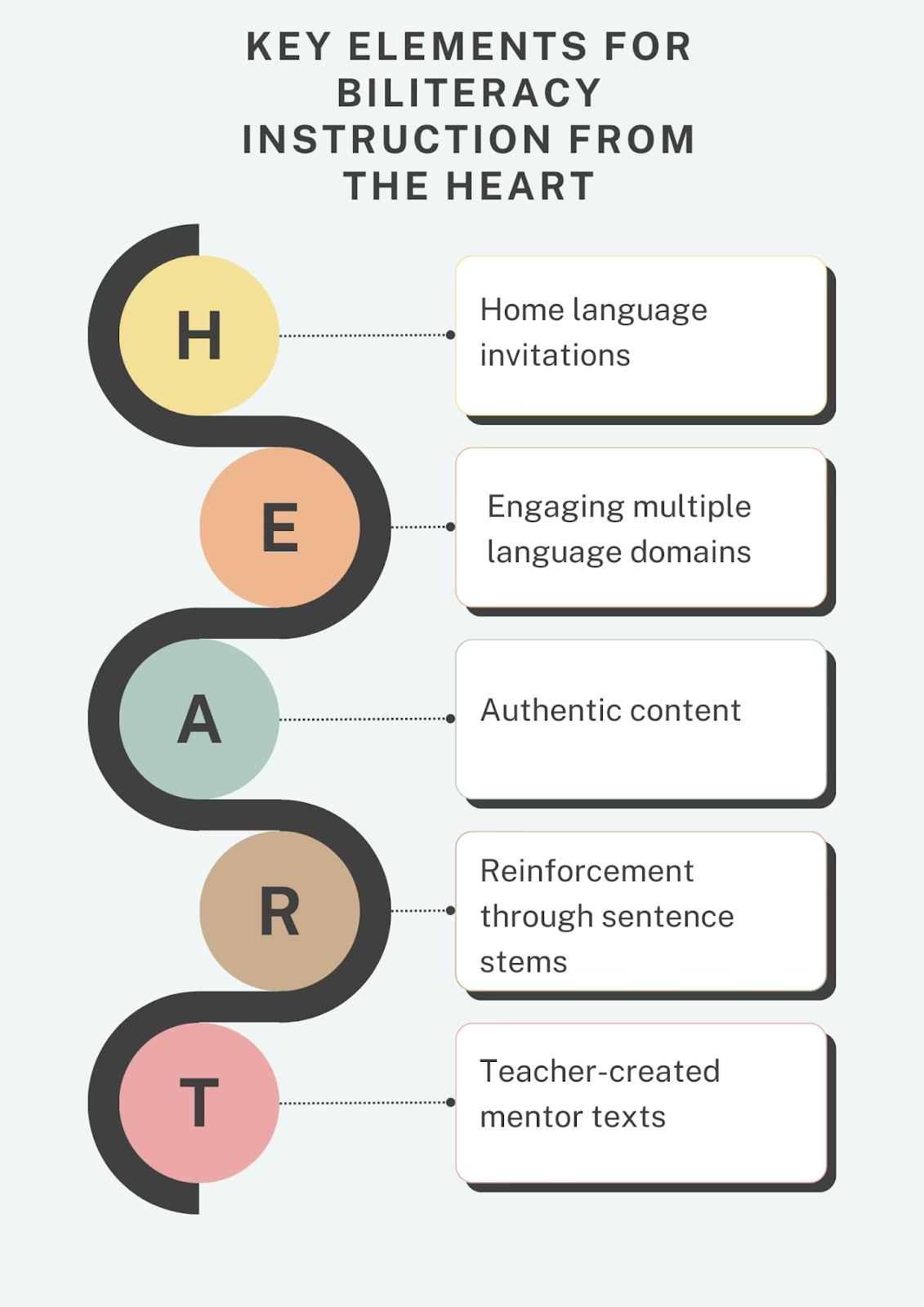

Dr. Stewart and her colleague have published two teacher-friendly articles to provide specific teaching ideas, presented as “Key Elements for Biliteracy Instruction” from the HEART strategies, for Polish (or any) teachers of newcomers in both English and Polish.

“We were purposeful to ensure these were journal articles that would be freely available to teachers of displaced students in Poland and around the world.”

By employing strategies like heart maps, biographical poetry, and student-created projects, teachers can create spaces for meaningful engagement. “These activities allow students to feel valued and give them the tools to not only learn Polish but also share their unique stories,” Stewart explains. Such strategies also ensure students do not feel alienated, preserving their cultural identities while gaining the language skills they need to thrive in their new environment.

Teacher Shortages and Resource Challenges

As promising as these biliteracy initiatives are, they exist within a broader context of systemic challenges. Poland’s educational system, like many others around the world, is grappling with teacher shortages. This shortage, exacerbated by the influx of refugee students, has placed additional strain on already overwhelmed schools.

Initially, the Polish Ministry of Education set up preparatory classes within primary schools, Dr. Stewart explains. These were special classes just for newcomers and the Polish Ministry of Education also hired teacher assistants for these classrooms which they call cultural assistants who are also displaced from Ukraine. However, the number of these classes is dwindling due to funding.

“One teacher I worked with was told she could no longer have a preparatory class for newcomers—they were canceling it due to funding,” shares Dr. Stewart. “While she wanted to continue teaching displaced students, she was moved to a general education class instead. It was heartbreaking.”

The shortage of teachers with the specific skills needed to teach non-native speakers has led to increased workloads for those already in the system. Poland, which was already dealing with an aging teacher workforce and budget constraints before the war, is now having to manage the sudden increase in students without sufficient resources.

Additionally, the role of “cultural assistants”—who were often Ukrainian speakers helping both students and teachers bridge the language gap—has dwindled as funding becomes scarce. These assistants were crucial in the early phases of integration, using their language skills and shared cultural backgrounds to help the refugee children transition.

To address these challenges, Stewart and her colleagues are developing a free teacher training manual that will be available online, offering practical solutions and curriculum support for educators of displaced students.

“We want to give teachers worldwide access to resources that help them better serve students who are navigating displacement,” says Dr. Stewart. However, the effectiveness of these solutions depends on securing adequate funding for bilingual educational materials and other resources.

Beyond individual initiatives like Project Biliteracy, there is an urgent need for systemic reform. Dr. Stewart emphasizes that without targeted funding from both the Polish government and international aid, these efforts will remain patchwork solutions. “Teachers are doing incredible work with what they have, but we need to ensure sustained resources are available so they can continue providing the support these students need.”

Transitioning from Remote Learning to In-Person Education

For many Ukrainian refugee children, the transition from remote learning during the pandemic to in-person education in Poland is more than just a shift in learning format—it’s a complete upheaval of their lives. These students have endured multiple layers of disruption: from the pandemic to the war, from leaving their homes to starting over in a new country with a different language and culture.

“There are just so many changes to consider,” says Dr. Stewart. “These children have lived through the pandemic, war, and separation from their families, all while adjusting to a new language and educational system. It’s a lot for anyone, let alone a child or adolescent.”

The emotional toll of these transitions cannot be understated. Many of these children have been separated from family members, particularly fathers who stayed behind to fight in Ukraine. Coupled with the trauma of displacement, these factors create a delicate situation in which students need not only academic support but also emotional and psychological care. Schools and educators must be mindful of this, incorporating empathy and sensitivity into their approach to teaching displaced students.

Research indicates that refugee children often suffer from PTSD and other trauma-related disorders, making it harder for them to concentrate and engage in learning. Dr. Stewart notes that for some students, the emotional scars of displacement are compounded by the practical challenges of adapting to a new education system.

“These children need much more than language support—they need social and emotional care to help them process what they’ve been through,” she says.

Unfortunately, many schools lack the resources or trained staff to address these needs comprehensively.

ited to the classroom. At the policy level, there is a pressing need for systemic changes that recognize the unique needs of these students. Language support, cultural affirmation, and access to resources are essential components of any effective policy aimed at integrating refugee children into the education system.

“We need policies that don’t just ask these children to adapt to Polish culture but also celebrate their home cultures,” Dr. Stewart insists. “Maintaining their home languages while learning Polish is crucial for their success.”

Polish policymakers must prioritize funding for bilingual programs, teacher training, and the development of curriculum materials that cater to the needs of refugee students. Schools also need to establish policies that engage with refugee families, helping them navigate the education system and feel included in their children’s academic journey.

Equally important is the role of the broader community. Teachers, administrators, and local organizations can play a critical role in supporting refugee students and their families.

“It’s essential to build bridges between the community and schools so that students and their families feel welcomed,” Stewart emphasizes.

Embracing Refugee Students’ Futures

Despite the myriad challenges facing Ukrainian refugee children in Poland, one fact remains clear: these students bring with them a wealth of skills, experiences, and cultural knowledge that can enrich Polish classrooms. They possess resilience, linguistic diversity, and cross-cultural competence that many of their peers do not.

“They are brilliant students,” says Dr. Stewart, “and they bring transnational skills that give them a unique perspective on the world. We should not ask them to give up their language or their culture. They have so much to offer.”

For Polish schools, educators, and policymakers, the task is not simply to integrate these students but to recognize and build upon their strengths. By providing the necessary support—through biliteracy programs, teacher training, online learning resources, and community engagement—Poland can ensure that Ukrainian refugee children thrive in their new educational environment.